Welcome to the website dedicated to the

Nominal Structures of Uralic Languages

You will find a collection of analyzed data here, arranged into linguistic modules, which aims to provide a structured empirical basis for descriptive, comparative, typological and theoretical studies on nominal syntax. At its present state, the database contains original language data from Modern and Old Hungarian, Eastern and Northern Khanty, Tundra Nenets, and Udmurt. All the examples are glossed and translated into English. Hopefully, the design of the presentation will help you to compare the structures in these languages and to simultaneously study the linguistic phenomena you are interested in.

You can read more about the concept of the database and about the research project behind. The section on data display and glossing explains how the individual items of this database are to be interpreted. You can navigate among various topics using the menu on the left. When you arrive at a certain parameter where language data illustrate the phenomenon under discussion, you can switch between languages at any time using the tabs on the top. You will find a button on each page with original language data which allows you to export the data you need directly.

The database in its present form contains 428 items of original language data illustrating 436 phenomena.

About the Database

This open access database collects original language data from various Uralic languages, namely from Modern and Old Hungarian. Eastern and Northern Khanty, Tundra Nenets, and Udmurt.

The data are arranged into previously established linguistic modules. The hierarchical structure of linguistic topics, subtopics and parameters reflects the fundamental concept of the database that is to offer an annotated empirical basis for the study of nominal syntax, be it comparative, typological or theoretical in nature. The selected data can be divided into two larger groups, which are of course interrelated. One group of the topics covers copular clauses and nonverbal predication in general. The other group of topics covers the internal properties of noun phrases, with special attention to adnominal modification patterns, quantification and determination. The topics, as a principle, concentrate on structures and syntax, which means that lexical and morphophonological peculiarities are ignored, unless relevant for syntactic variation. The presentation of the data was designed in a way that the users may navigate among various topics any time, using the “Topics” menu on the left. As for the grammatical categories and terminology used throughout the database, we tried to stick to basic structural concepts and to common and widely accepted descriptive terms. Description is principally limited to distributional properties without going into more theory-driven analysis (admitting, however, that a completely theory-neutral description hardly exists). At the same time, descriptive traditions of individual Uralic languages could not be taken into consideration, and uniformity in our approach was a conscious decision in this respect. A great advantage of the present website is that, unlike several other digitized corpora of these languages, this database is fully available in English including explanations, glosses and translations of the original data.

Find more information about the source languages and about how the individual items in the database are displayed.

The research project behind the database was a project with the same title, Nominal Structures of Uralic Languages, funded by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH 125206) between 2017 and 2021 (with an extension, due to Covid, to 2023). The project as well as the database has been hosted by the Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics (former Research Institute for Linguistics, Hungarian Academy of Sciences).

The project aimed to integrate data analysis, descriptive tasks and theoretical discussion regarding all constructions that have the noun as their core element in a selected group of Uralic languages. The members of the research team were all theoretical linguists and/or linguists who are experts in one or two of the relevant languages, working on a wide range of research topics, which were all related in a way to nominal syntax. As a result of group discussions, several new comparative and theoretical research questions have arisen at each level of investigation; just to name a few: the so called belong-constructions, ellipsis, the parameter of head-finality, as well as more specialized issues concerning e.g. the nature of determiners and the copula in these languages.

You can check the homepage of the project itself to get more information about the participants, as well as about the talks, publications, and the new theoretical results related to the research group.

Principal investigator and host of the database

- Barbara Egedi

Researchers who cooperated in building the database

- Erika Asztalos

- Márta Csepregi

- Ekaterina Georgieva

- Veronika Hegedűs

Database design and development

- Csaba Merényi

About Data Display and Glossing

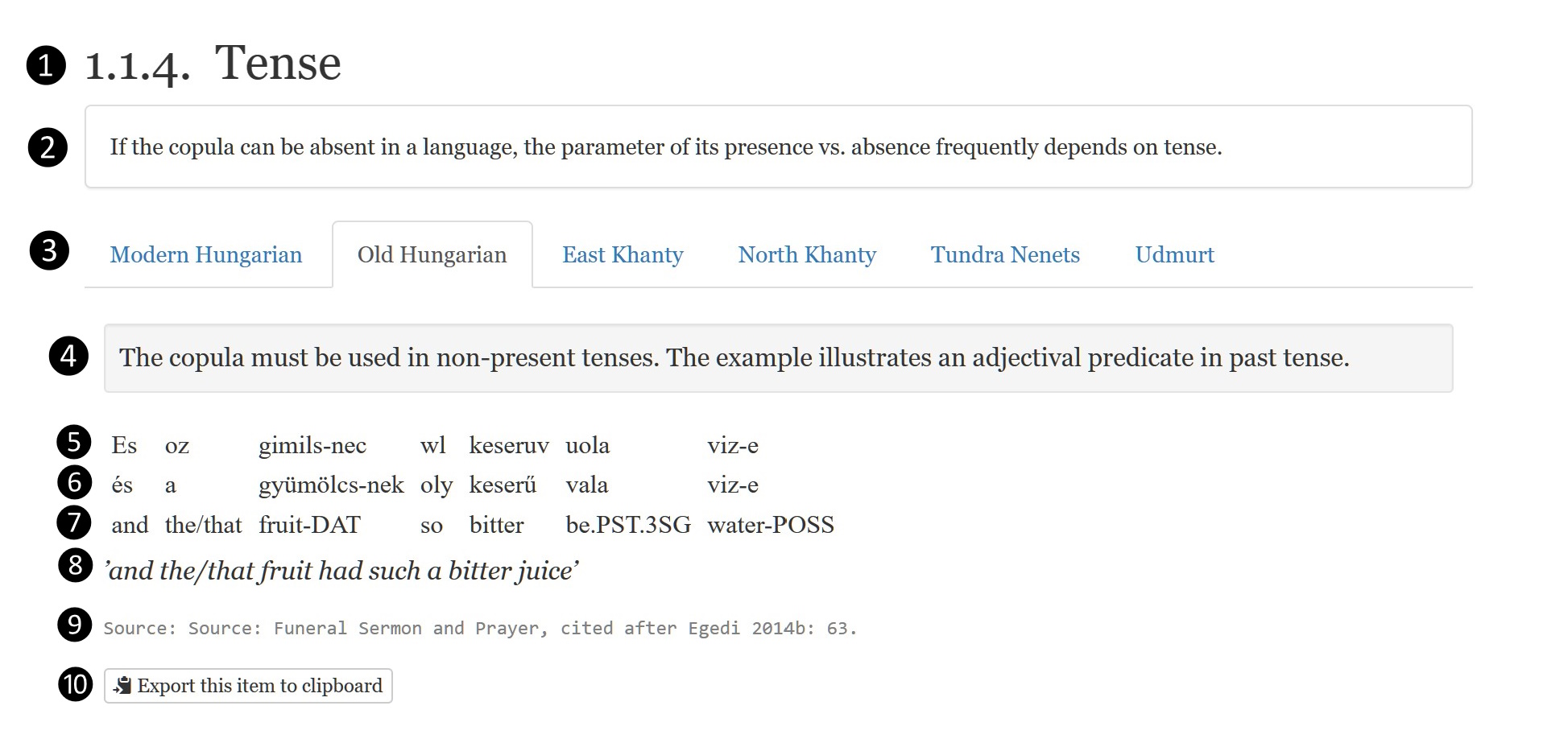

The database provides separate, annotated examples from a number of Uralic languages according to relevant, linguistically defined parameter-settings. In what follows, we explain how the individual items in the database have been designed and how to interpret the presentation of data (➊ - ➓ ).

After choosing the ❶ topic you are interested in and the parameter-setting(s) that might influence how certain grammatical properties appear in a given language, you arrive at points in the database where original language data are presented to illustrate the phenomena under discussion. (Remember that you can any time switch between the languages using the ❸ tabs on the top.)

In the first line of each item you will find the ❺ original language data, either in the form as it was published, or in the form it was documented in fieldwork (in some sort of transcription). The form and orthography are always identical with the version we found in the source material (about the sources, see below). If the data has both an original orthography (e.g. Cyrillic, or characters transported from old manuscripts) and a ❻ scientific or normalized transcription, we provide both. All the examples are ❼ glossed and ❽ translated into English. Glosses representing the relevant linguistic analysis are provided under the original language data, aligned and followed by the English translation of the cited item. Importantly, the source is always indicated as part of the data-package.

At several places you will read “this parameter is not applicable”. This is because the parameter under discussion simply cannot be applied in that language. (For instance, post-nominal modifiers cannot be illustrated if all modifiers are pre-nominal.) We made efforts to add ❷ short explanations under the topics where this issue emerges in one or more languages.

If you see this short comment: “no data for this language yet” at certain points in the database, it can mean either of the following statuses: (i) we are still editing this part, (ii) we had difficulties with finding original data to illustrate the relevant phenomenon. The status of the node can easily change, of course. Please check back later for the data you need. We are also happy to get support from visitors of the website and to find new sources we are not familiar with yet.

The button ❿ “Export this item to clipboard” allows you to copy the item directly to your clipboard and insert it into a rich text enabled editor (e.g. a Word or RTF document). Feel free to use the data for your research, be it a scientific talk or a paper in a related topic.

The ❾ sources of the data come from an extremely diverse material, which precludes uniformity in citing. Thus the presentation of the original data always corresponds to the form it is presented in the source material we used. The latter can be any kind of published linguistic literature, but we also rely on other, publicly accessible databases. For instance, for Old Hungarian we invariably cite the data from the Old Hungarian Corpus, so we follow the conventions that have been established in that corpus. At the same time, Khanty examples might appear in a heterogeneous fashion, as not only is there a great inconsistency in their Cyrillic-based writings, but a considerable variation can also be observed in their ❻ scientific transcriptions. This means that the cited literature and corpora might use different transcriptions even for the same language variety. On the website of the Ob-Ugric Database, one can read about what is behind the diversity that the different transcribing traditions show. This page also offers further tools to navigate around the conventions and traditions. Most of the sources use modified versions of the so called Finno-Ugric transcription (FUT), or the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). Data have also been drawn from collections of individual researchers who elicited original language data through personal interactions with native speakers. For instance, Surgut Khanty data may come from language documentation carried out by Márta Csepregi, while the Udmurt data was partly collected by Ekaterina Georgieva, directly from Udmurt speakers. Some Modern Hungarian examples have been provided by one of the native speaker data editors.

If the original language data was not ❽ translated into English in the source material, one of the database editors translated it to keep the database uniform in this respect.

❼ Glosses were also adjusted and translated, when this was necessary. If the original language data has already had any kind of annotation in the source material (corpus or secondary literature), we retained as much as possible. As for the abbreviations used in glosses, we followed the list of abbreviations developed during the Uralic Languages under the Influence project running between 2016-2017 in the same Research Centre. The abbreviations there mainly follow the Leipzig Glossing Rules with additions where it was necessary.

We also used a few more conventions in the presentation of the ❺ original language data, where clear judgments on the (un)grammaticality of the relevant example could also be added:

| * | marks that the data is unacceptable by speakers, thus ungrammatical |

| ? | marks that the data is not fully acceptable, but is not completely ungrammatical either |

| *X/Y | marks that only the expression without the asterisk is acceptable in that position |

| (*X) | marks that the structure is only grammatical without the expression in parenthesis |

| *(X) | marks that omitting the expression results in an ungrammatical structure |

| % | marks that grammaticality judgments vary among speakers |

About the Languages

Ut sodales risus vel consequat hendrerit. Maecenas aliquam ipsum non turpis lobortis placerat. Proin ultrices laoreet orci, a sodales ligula porttitor et.

Hungarian

Hungarian belongs to the Ugric branch of the Uralic language family, its closest relatives being Mansi and Khanty varieties. According to the traditionally classification, the latter together form the Ob-Ugric branch as a separate group. Among Uralic languages, Hungarian has the largest number of speakers, probably more than 13 millions: about ten millions live in Hungary, while the rest of the speakers can mostly be found in the neighboring countries. Contrary to its closest relative languages spoken in the territory of Russia, a great proportion of Hungarian speakers is monolingual.

Hungarian dialects are mutually intelligible, although considerable differences can be found in vocabulary as well as in pronunciation. Regional standards can be easily identified. It must be noted, however, that a systematic research on the possible structural variation between any two dialects has not been carried out so far. The only exception to the uniformity of the dialects is Moldavian Hungarian (Csángó), a dialect spoken on the eastern side of the Carpathian Mountains, which was permanently isolated from standard Hungarian for historical reasons. This dialect has mainly survived in orality and has heavily been influenced by the Romanian majority language.

Hungarian is also the longest documented language in the Uralic family. As a rough approximation, at least three major historical language stages can be distinguished: Old Hungarian (896-1526), Middle Hungarian (1526-1772), and Modern Hungarian (1772-present day). The traditional division of the stages is linked up with historical events. From a linguistic point of view, a crucial source to begin with is the Letter of Foundation of Tihany, a charter from 1055, which survived in its original format and already contains more than 50 Hungarian words and word-groups.

Old Hungarian can be further subdivided into Early and Late Old Hungarian. The first stage mainly preserved sporadic records and only a few short, continuous texts. The first such text is the Funeral Sermon and Prayer from ca.1195. The second period, Late Old Hungarian from about 1370, already abounds in codices containing translations of Latin religious literature, and some original Hungarian compositions (documents, poems and letters) have also survived. These are long enough, uniform texts, each forming a closed corpus of their own, thus suitable for syntactic investigations. The Old Hungarian texts are all hand-written manuscripts, whose critical editions have been published and in several cases also republished, but the texts became digitally accessible and searchable only recently, via the Old Hungarian Corpus (Simon & Sass 2012, Simon 2014).

For the newest description of Hungarian grammar, consult the already published and forthcoming volumes of the series The Syntax of Hungarian. Comprehensive Grammar Resources at the Amsterdam University Press (Alberti – Laczkó 2018, É. Kiss – Hegedűs 2021.). A general introduction about the language itself can be found in the introductory chapter of each volume by István Kenesei, one of the series editors. For the position of Hungarian language within the language family and its relation to other Uralic languages, the following chapters of recent manuals are recommended to use: Abondolo & Valijärvi (2023b), Kenesei & Szécsényi (2022), Skribnik & Laakso (2022).

Literature on earlier stages of Hungarian have mainly been written in Hungarian, but recently more and more studies appeared in English on various syntactic phenomena of Old and Middle Hungarian (cf. inter alia É. Kiss 2014b). Moreover, the diachronic syntax of Hungarian has become an important and constant focus of research in the Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics, birthplace of the present database as well. Historical corpora have also been developed to make data more accessible and to advance the work on theoretical questions. Besides the Old Hungaroan Corpus, the most relevant is the Historical Corpus of Hungarian Private Language (Novák et al. 2013, 2018). You can find further corpora and databases browsing this collection provided by the Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics. The corpora are open to search, free of charge, but at the time being, monolingual.

East Khanty

Eastern (or East) Khanty, together with Mansi and other varieties of Khanty, belongs to the Ob-Ugric subgroup of the Ugric branch of the Uralic language family. According to the Russian Census of 2010, Khanty (including its Eastern and Northern varieties) is spoken by 9 584 speakers, while the number of self-declared ethnic Khantys is 30 943. Khanty is classified as “endangered” in the Ethnologue database. Russian has had a strong influence on the language, and nowadays, there are practically no monolingual Khanty speakers.

Eastern Khanty is spoken in a vast territory in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Regions of the Russian Federation. The term Eastern Khanty actually refers to a dialect group consisting of Surgut Khanty (with less than 3000 speakers), Vakh Khanty (with around 200 speakers), and two nearly extinct dialects, Salym Khanty and Vasyugan Khanty. Surgut Khanty can further be divided into four, mutually intelligible varieties: Pym Khanty, Tromagan Khanty, Agan Khanty, and Jugan Khanty, spoken along the eponymous rivers. Speakers of the former three varieties are mostly reindeer herders, while Jugan Khantys rather fish and hunt for a living.

Surgut Khanty has a literary norm, with Cyrillic orthography being used (with some additional characters and diacritics). The first written Cyrillic standard was developed in the 1990s, while a second Cyrillic orthography was established a couple of years ago by A. S. Pesikova and N. B. Koškarëva. The traditional transcription used for scientific purposes is based on the Uralic Phonetic Alphabet.

For more details, consult the following chapters of recent manuals: Schön & Gugán (2022), Skribnik & Laakso (2022), Csepregi (2023).

Corpora and databases:

North Khanty

Northern (or North) Khanty, together with Mansi and other varieties of Khanty, belongs to the Ob-Ugric subgroup of the Ugric branch of the Uralic language family. It is spoken by the lower Ob and its tributaries Kazym, Kunovat, Synja, etc., in the Yamalo-Nenets and the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Regions of the Russian Federation. Traditionally, Northern Khanty, depending on the area where they live, are reindeer herders or fish and hunt for a living.

According to the Russian Census of 2010, Khanty (including its Eastern and Northern varieties) is spoken by 9 584 speakers, while the number of self-declared ethnic Khantys is 30 943. Khanty is classified as “endangered” in the Ethnologue database. Russian has had a strong influence on the structure and use of Khanty, and nowadays, there are practically no monolingual Khanty speakers. Northern Khanty has also been influenced by Mansi, Komi, and Nenets.

The term Northern Khanty actually comprises a dialect group consisting of different subdialects (Šerkaly, Kazym, Berezov, Obdorsk), which form a continuum. Kazym Khanty has a literary standard and a dominant position in Khanty-language publication activities. In literacy, Cyrillic script with some special characters and diacritics is being used, however, there is considerable variation in the orthography systems both within and across the subdialects and even Kazym Khanty lacks a uniform orthography. The traditional transcription used for scientific purposes is based on the Uralic Phonetic Alphabet.

For more details, consult the following chapters of recent manuals: Sipos (2022), Skribnik & Laakso (2022), Csepregi (2023).

Corpora and databases:

Tundra Nenets

Tundra Nenets belongs to the North-Samoyedic group of the Samoyedic branch of the Uralic language family. Officially, it is regarded as one single language together with Forest Nenets, however, recent linguistic data suggest that they are separate languages rather than two dialectal variants of the same language. Tundra Nenets is mainly spoken in the Nenets Autonomous Region, in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Region and in the Taimyr District of the Krasnoyarsk Territory, but small groups of Tundra Nenets also live in the Arxangel’sk province, in the Komi Republic, and in some parts of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Region. According to the Russian Census of 2010, Nenets (including Tundra and Forest Nenets) is spoken by 9 584 speakers and the number of self-declared ethnic Nenets population is 44,640, the majority of which (around 42 600 people) are Tundra Nenets. The traditional occupation of Tundra Nenets is reindeer herding, which involves a nomadic lifestyle.

Tundra Nenets is taught in some elementary and middle schools and in higher grades, and the language has been increasingly used on audiovisual and electronic media. Nevertheless, its use is very limited in public domains and the language is classified as “endangered” in the Ethnologue database.

Tundra Nenets can further be divided into Western, Central, and Eastern dialectal groups, which show differences at all linguistic levels but are mutually intelligible. Russian has had a strong influence on Tundra Nenets, and Tundra Nenets has also had contacts with Komi and Khanty.

Tundra Nenets has a written standard based on the Cyrillic alphabet. Although textbooks and manuals, original and translated literature, and periodicals have been regularly published in Tundra Nenets, the range of functional styles and uses is still limited in the language, and there are still some unresolved problems with its standardization.

Recent descriptions of Udmurt: Nikolaeva (2014), Burkova (2022), Wágner-Nagy & Szeverényi (2022), Mus (2023).

Corpora and databases:

Udmurt

Udmurt belongs to the Permic branch of Finno-Ugric languages, its closest relatives are Komi-Zyrian and Komi-Permyak. Udmurt is mainly spoken in the Udmurt Republic of Russia, where it is a minority language, and in the neighbouring administrative areas of the Russian Federation (Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, Mari El, and the regions of Perm, Kirov, and Sverdlovsk). According to the 2010 Russian Census, Udmurt is spoken by 324 338 speakers in the territory of Russia, while the number of self-declared ethnic Udmurts is 552 299. Since 1990, Udmurt has had the status of official language in the Udmurt Republic (besides Russian), however, its usage is limited in public spheres. Udmurt is taught in some (mainly rural) schools as a subject, and is used on some platforms of mass media and on the Internet.

Russian has had a strong influence on Udmurt, which manifests itself at all linguistic levels. Nowadays, practically all native speakers of Udmurt are bilingual, as they also speak Russian at a native or near-native level. Udmurt is classified as “endangered” in the Ethnologue database. Udmurt forms part of the Volga-Kama Sprachbund, together with Mari, Mordvin and Komi (Finno-Ugric), and Chuvash, Tatar, Bashkir (Turkic).

Udmurt dialects fall into four groups: Northern, Central, Southern, and Peripherical dialects, with differences at all linguistic levels but mutual intelligibility. Beserman (spoken in Northern Udmurtia) has traditionally been considered as a dialect of Udmurt but its speakers define themselves as a distinct ethnic group (for classifying Beserman as an independent language, check this website.

The literary variant of Udmurt was created in the 1920s. The present-day orthography is Cyrillic with some additional diacritics on certain characters. As systems of transcription, Uralic Phonetic Alphabet (also known as Finno-Ugric transcription) and, in the Russian and Udmurt language literature, Cyrillic phonetic alphabet are mainly used.

Recent descriptions of Udmurt: Edygarova (2022), Suihkonen (2023).

Corpora: